I’ve been speaking English my whole life. But it wasn’t until recently that I realised that I cannot pronounce the letter “w.”

The ghost of YouTube algorithms once suggested a short video from a Vietnamese woman who now lives in Germany. Uyen Ninh‘s videos poke fun at the cultural differences between Germans and Vietnamese, and through her perspective, I’ve learned that Indians and Vietnamese have a lot in common.

Scrolling through the comments section of the videos, I learnt that people and cultures around the world have remarkably similar belief systems.

It was in one of these videos that I heard her German partner exclaim, “I cannot pronounce ‘W’!” As with most of her videos, I scrolled through the comments section. Many people agreed, and understood that non-English speakers pronounced the first syllable of “Valley” like “Wallet”. And that’s when I realised I couldn’t tell the difference.

A Medley of Languages

At home, my grandmother spoke to me in Tamil. So whatever little Tamil I now know is thanks to her. My parents alternated between Tamil and English. And growing up in Delhi Cantonment, I was surrounded by people who spoke English fluently. Hindi, however, was a very different ball game. I struggled terribly and couldn’t wait till I reached the ninth grade, when I was allowed to drop Hindi from my curriculum and elect Sanskrit as my second language. In a TamBrahm household, Sanskrit is much easier than Hindi!

Eventually, though, I had to move out of this bubble. What my school couldn’t teach me, interacting with (and getting married!) outside my community, did. My only regret is not knowing my own mother tongue Tamil very well, especially reading and writing. So whenever someone in a family WhatsApp group types in Tamil, I try my best to read it—it takes forever, but that’s about the only way to stay connected to my roots.

I find Uyen’s playful skits on living with cultural differences extremely relatable. Everyday decisions like what to eat, what to wear, how to talk and how to celebrate festivals becomes tricky. However, Uyen reminds me that my struggles are tiny compared to hers!

Let’s get back to the “W” that Uyen’s German partner couldn’t pronounce. I did what anyone else would do and searched online. Here’s what an AI generated response told me:

The key difference between the sounds represented by “v” and “w” lies in their articulation: “v” is a voiced labiodental fricative (bottom lip lightly touches top teeth), while “w” is a voiced bilabial approximant (lips rounded and slightly protruded).

I stared hard at this explanation, and tried to say ‘V’ and ‘W’ a few times. Wait. How does one say ‘w’? When we learn the English alphabet, w is pronounced “double u.” How on earth are we to know how to pronounce it? So I tried a few words that started with ‘w’. I tried listening to the sounds on the internet, but they sounded the same as ‘v’! So, I gave up. As long as the person I was talking with knew what I was saying, how did it matter whether my lip touched my tooth or not!

The key here is that these letters sounded the same to me, but not to a native speaker. This is perhaps how most of the world feels when they hear sounds like ‘zh’ that are exclusive to Malayalam and Tamil (well, technically, it’s Tamizh). My husband tries hard to learn the sound, but he eventually ends up saying ‘ra’ instead. For reference, here’s what it sounds like:

Each language has its idiosyncrasies. A family of languages tends to share some similarities. But what if your native language is entirely different from someone else’s?

Someone who understands Hindi will probably be able to grasp 20-30% of Bengali or Punjabi, since they originate from Sanskrit. Tamizh, a Dravidian language is said to have completely different roots.

That Tamizh and Hindi have very little in common is something I can attest to. Hindi was (and still is) hard. The grammar and the script is completely different from English and Tamizh.

Learning a New Language

A little under a year ago, I began learning Spanish on Duolingo, quite by accident. One of my clients told me Duolingo had a great onboarding experience, and so, out of curiosity, I signed up. The app made learning Spanish fun, and I got hooked. As of today, I’m on a 332 day streak. What can I say, that owl is persuasive!

What’s more, I found Spanish fairly easy. For starters, the script is the same as English. The only difference lies in the accents that I’m still trying to figure out. But unlike English, it is phonetic, so pronunciation is a breeze. And the best part, no need to worry about w, or even k!

English, Hindi and Tamizh have very different grammar rules and scripts. Each also has different sets of sounds, not found in the other language, giving a multilingual person like me an edge while learning a new language. Apart from sounds, it also offers a broader vocabulary to refer to, to form connections.

Many English words are the same in Spanish, with the addition of suffixes. For example:

- Usually becomes ususalmente, normally becomes normalmente.

- Fantastic is fantastico, perfect becomes perfecto, rapid becomes rapido.

As for inanimate objects having a gender, that’s there in Hindi too. In fact, some words in Spanish are nearly identical to Hindi/Sanskrit, including the gender:

- Table (English) = Mesa (Spanish) = Mez (Hindi)

- Shirt (English) = Camisa (Spanish) = Kamiz

- Room (English) = Sala (Spanish) = Shala (Sanskrit/Hindi)

- Orange (English) = Naranja (Spanish) = Naranga (Sanskrit)

And, I recently found out the word for rice (arroz) comes from the Tamil word arisi.

The Spanish consonant ñ exists in Sanskrit/Hindi and Tamil.

I’m sure if we dig further there will be other similarities.

Finding Common Ground

There is a lot of ongoing debate about which language is older, Sanskrit or Tamizh. As this fascinating video from Storytrails points out, that question is often seen from an ideological lens.

When it comes to culture, everyone wants to be the oldest! It seems to be some sort of ego-massage to claim that something came first. But honestly, who cares? If anything, a language that’s extremely old is likely dead. That we speak English—a language that has constantly evolved and incorporated words from several languages is proof that to be relevant, it must work. The idea of language is, after all, to communicate.

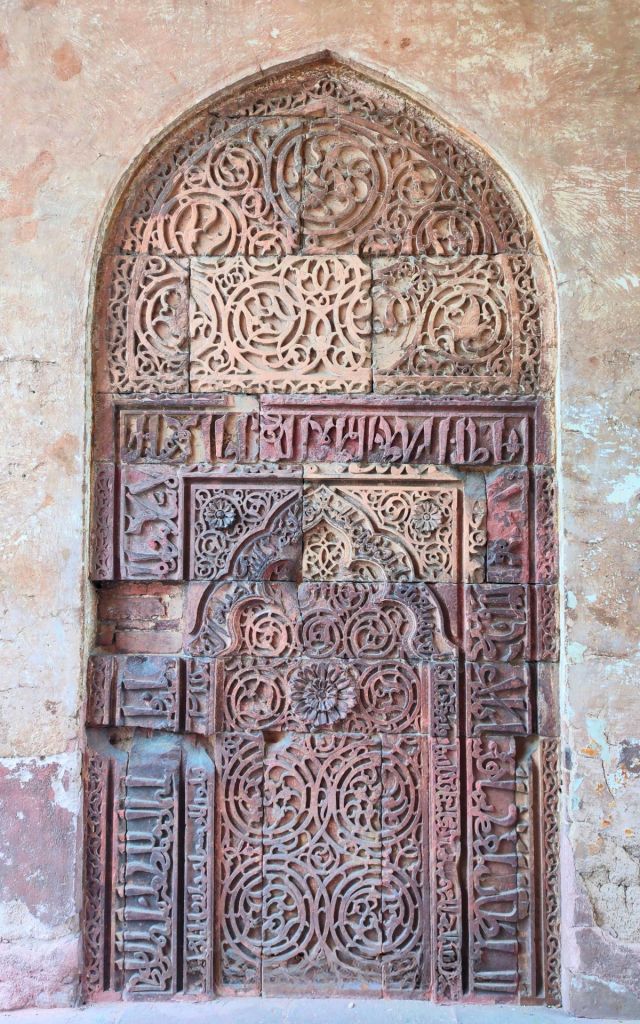

Language and culture cannot exist in isolation. If we must go back in time, then we must also go back to a time when people exchanged and adopted ideas. The similarities we find today between different cultures is because of ancient trade. Ironically, in a globalised world we’re increasingly becoming resistant to such evolution.

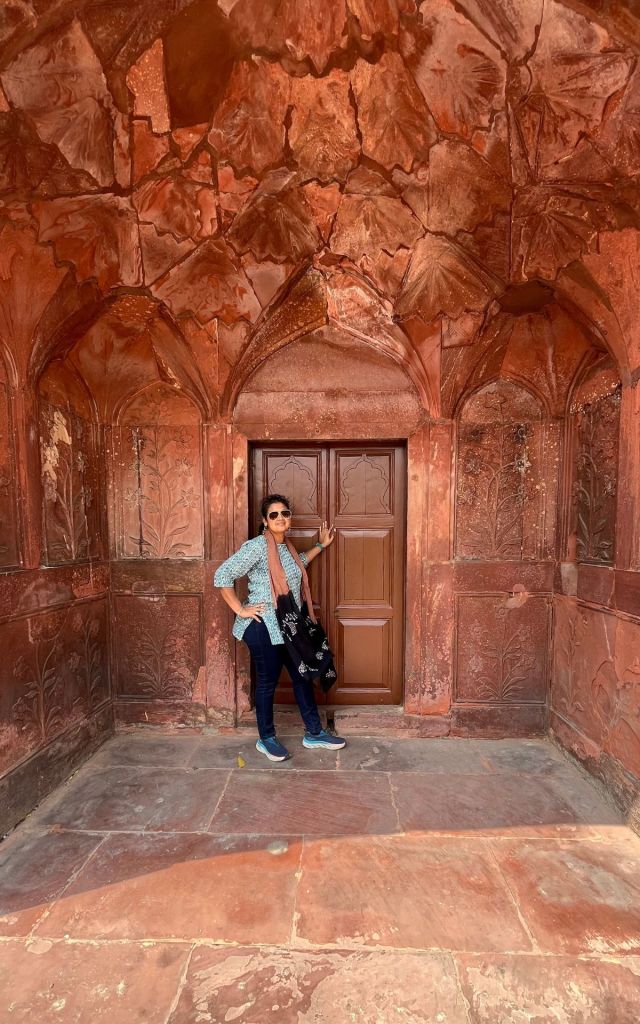

A few months ago, we visited Mexico and I tried to practice some words at the resort we stayed in. The locals were extremely appreciative of the effort I was putting in and encourage me to speak. It turned out, many of them were learning English on Duolingo too!

It will be quite a while before I can get truly fluent in Spanish—that would need real world practice, but for now, I am happy discovering the surprising similarities between languages and cultures around the world. (Apparently there is a lot of similarity between Tamil and Korean!)