India’s cultural history dates back to prehistoric days. Yet, when it comes to design, the world seems to consider Europe as the centre for excellence.

The India Art, Architecture and Design Biennale 2023 (IAADB23) was a welcome initiative by the Ministry of Culture to show the world (and more importantly, to Indians) what they’ve ignored (or perhaps wilfully tried to destroy, almost succeeding at it).

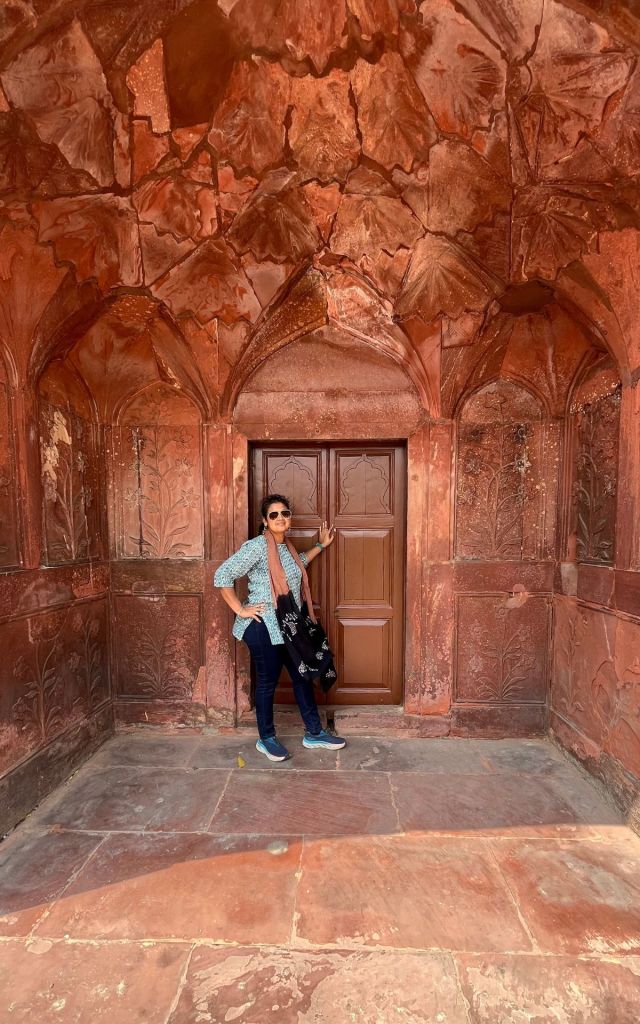

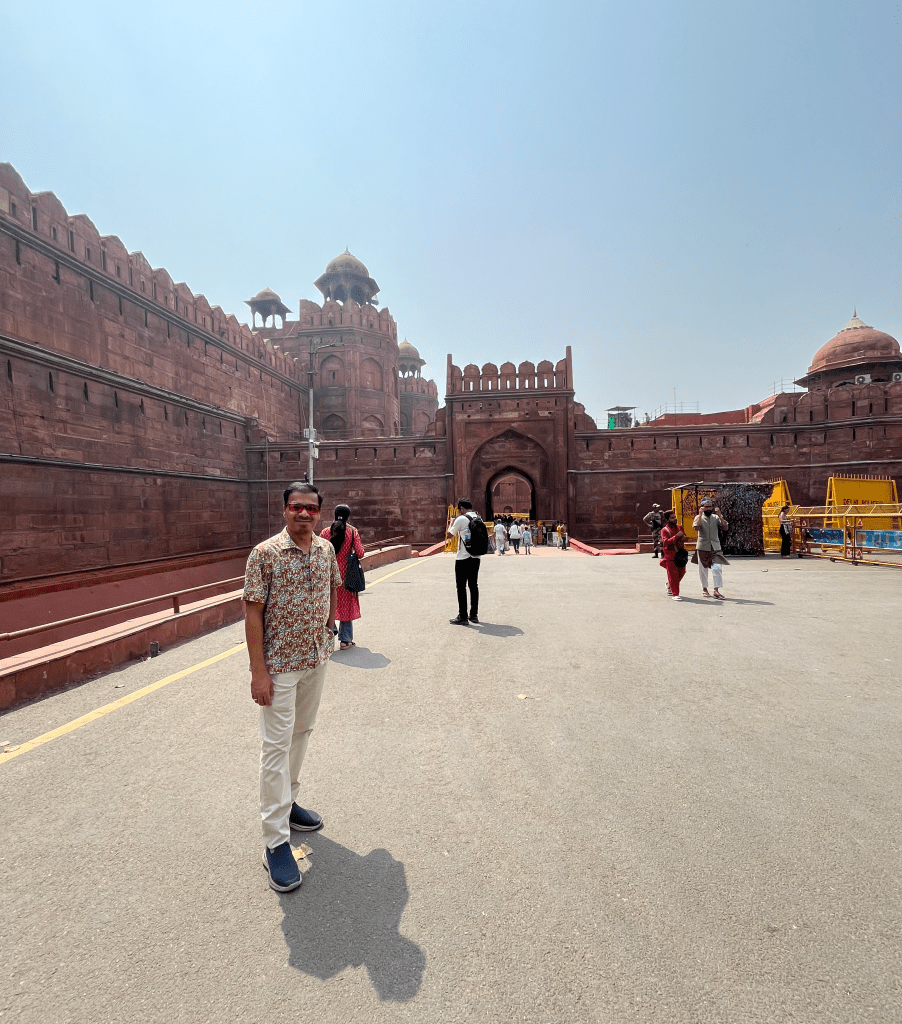

The initiative captured public imagination. From quirky installations to mind-blowing paintings, and from replicas of temples to modern art, there was something for everyone.

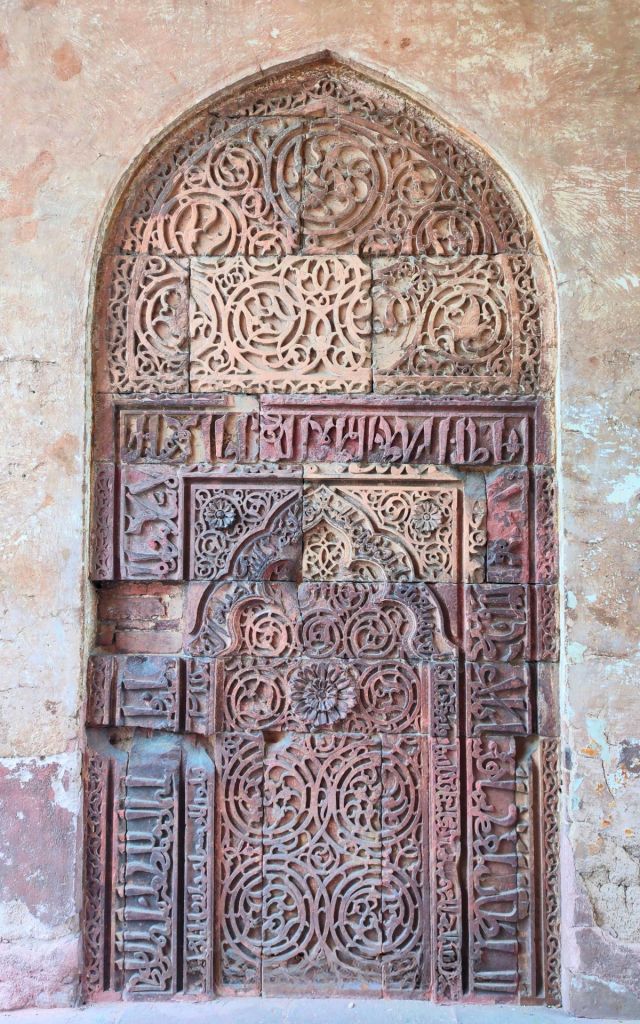

The Red Fort, with its sprawling lawns and numerous barracks was an appropriate choice. To house the cultural history of a nation as rich and diverse as Bhaarat, would have taken nothing short of a small army.

The entire showcase was divided into seven pavilions, each with appropriately beautiful names:

- Pravesh (Doors of India), Rite of Passage.

- Bagh-e-Bahar (Gardens of India), Gardens as universe.

- Sampravah (Baolis of India), Confluence of Communities.

- Sthapatya (Temples of India), Antifragile Alogrithm.

- Vismaya (Architectural Wonders of Independent India), Creative Crossovers.

- Deshaj (Indigenous Design), Bharat x Design.

- Samatva (Women in Architecture and Design), Shaping the Built.

While the installations at Vismaya and Pravesh made it to Instagram reels, Deshaj was the one that I was looking forward to. But the pavilion that ultimately had the biggest impact on me was Samatva.

Samatva: Shaping the Built

Curator Swati Janu introduced Samatva thus:

The root of the word Samatva (Sanskrit: समत्व) is sama (सम) meaning ‘equal’ which forms the essence of this exhibition and the reason why we showcase women architects here.

Historically and even today women have not been given the same opportunities and recognition as men in the fields of design, architecture and planning, be it in pursuing the profession or being widely published or invited to speak at panels.

Even before we entered the pavilion, we saw these graphics reminding us about the poor representation of women in architecture.

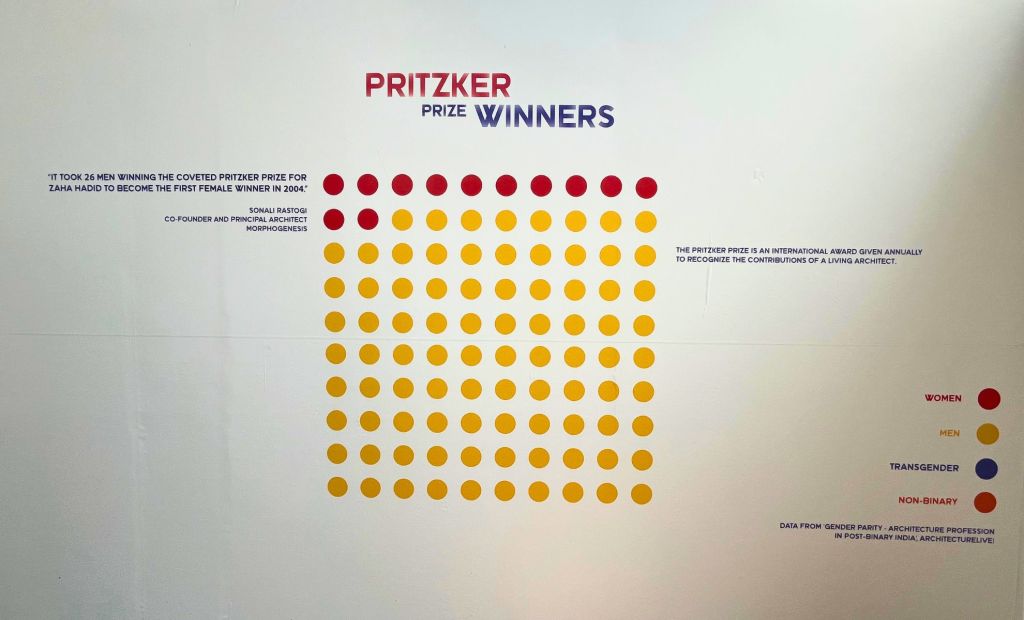

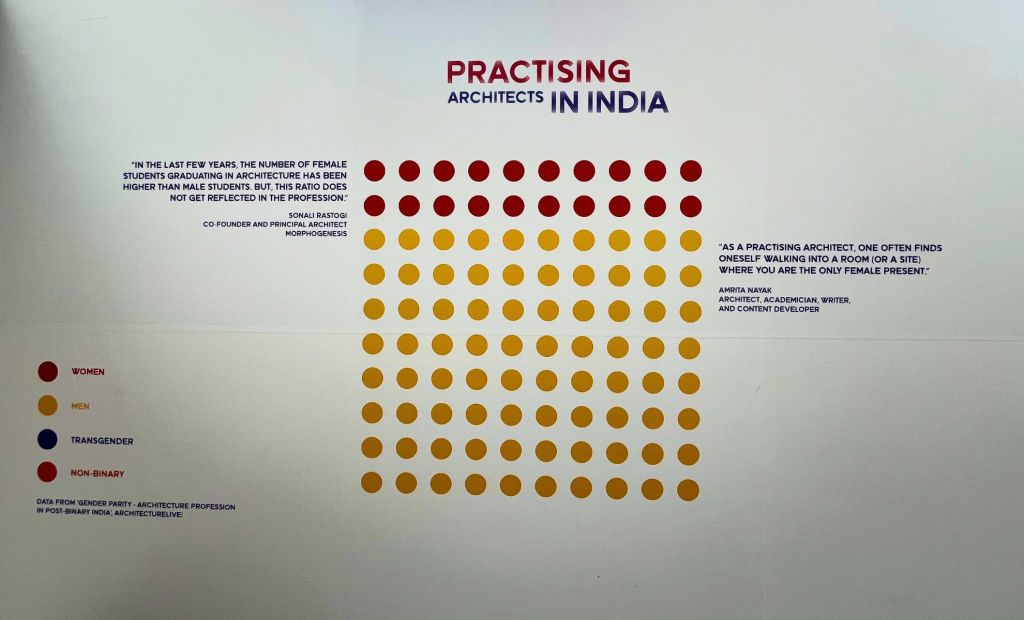

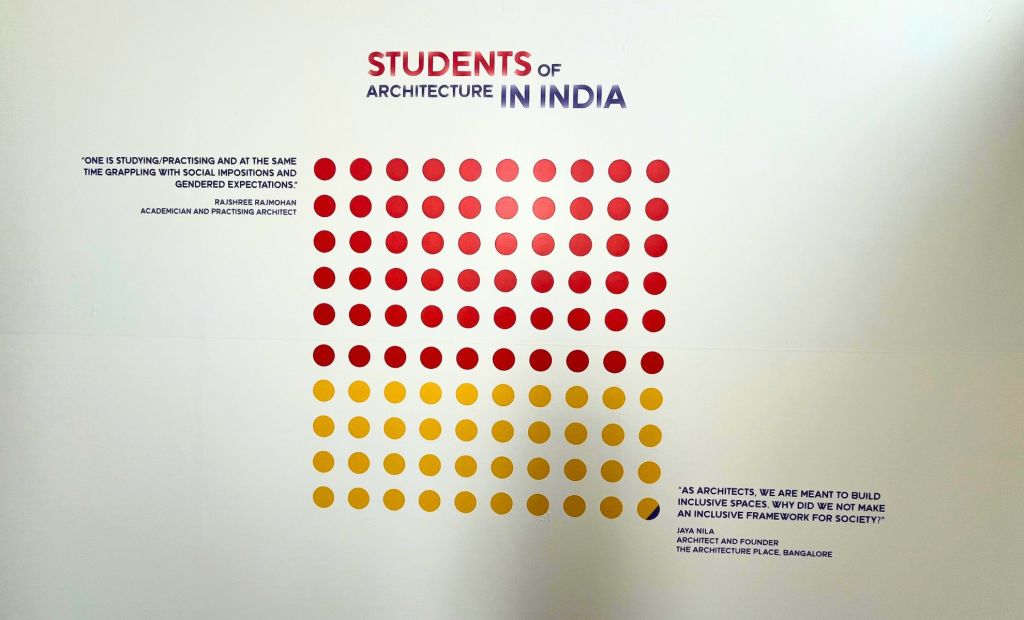

The information visualisation nerd in me, however, couldn’t help but appreciate how beautifully well the information was presented. Using nothing but coloured dots, the series of graphics showed the gap in gender participation in architecture. Yellow dots represented men, while red ones represented women. The saddest visualisation was entirely yellow.

Since 1972, there hasn’t been a single non-male president of Council of Architecture.

As architect Amrita Nayak puts it, “Often women have to work harder to be ‘listened to’ by senior leadership, in comparison to men with similar expertise or experience.”

I have been fortunate to have been heard in my work environment. But Amrita’s experience is all too familiar in a social setting.

The picture gets somewhat better when it comes to recognition of women in architecture, with 12 red dots against 88 yellow ones. The Pritzker Prize is an international award given annually to recognise the contributions of a living architect.

“It took 26 men winning the coveted Pritzker Prize for Zaha Hadid to become the first female winner in 2004.” – Sonali Rastogi, Co-Founder and Principal Architect, Morphogenesis

One reason why so few women have been awarded the prize is because there are fewer women who practice. 20 red dots to 80 yellow ones.

Beside the visual, another eerily relatable observation by Amrita reads, “As a practising architect, one often finds oneself walking into a room (or a site) where you are the only female present.”

“As architects, we are meant to build inclusive spaces. Why did we not make an inclusive framework for society?”

– Jaya Nila, Architect and Founder, The Architecture Place, Bengaluru

Amongst this sea of yellow dots, one visual represents hope. On the graphic for the number of students of architecture in India, the sixty red dots outnumber the yellow ones—a fraction short of forty. A tiny fraction of blue comes in too, to represent the transgender section of society.

However, as academician and architect Rajshree Rajmohan points out, “One is studying/practising and at the same time grappling with social impositions and gendered expectations.”

Equanimity is a concept that is rooted in Indian culture, but centuries of colonialism slowly eroded it. But hope springs eternal, and there are some signs of revival. We have a long way to go to rediscover our roots and I hope initiatives like IAADB don’t get restricted to quirky social media shorts but spark genuine conversations around design in Bhaarat.

This is the first of what will likely be a long series of posts dedicated to IAADB23, as I have just stumbled upon the treasure of memories in my digital archives. Stay tuned for more!