Growing up in a newly liberalised India, I watched a lot of American sitcoms. Most shows were reruns of old seasons. The exception being the last season of Friends which aired only a day after the US release. It was through these shows that I learned to associate tattoos with a certain persona. And that persona was not remotely Indian or tribal.

It was only after I left the bubble of the community in which I grew up, that I learnt how tattoos were commonplace in rural areas of the country—especially family names and religious symbols like ॐ (aum). But it wasn’t as glamorous as the tattoos I saw on foreigners.

A few years ago, I learned about the Māori practice of Tā moko through a wonderful (and particularly rage-inducing) podcast titled Stuff the British Stole. Tā moko tattoos looked beautiful. That they held deep meaning and weren’t just superficial marks to look cool, made them even more majestic. No wonder the tattoo artist was considered sacred.

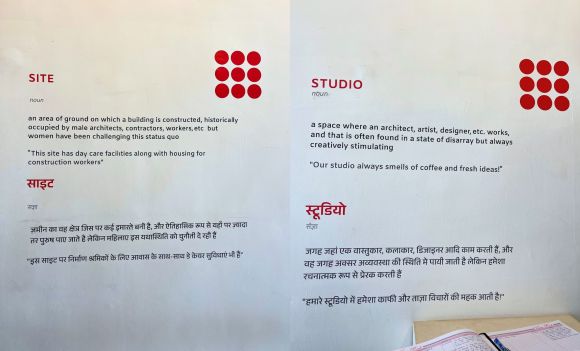

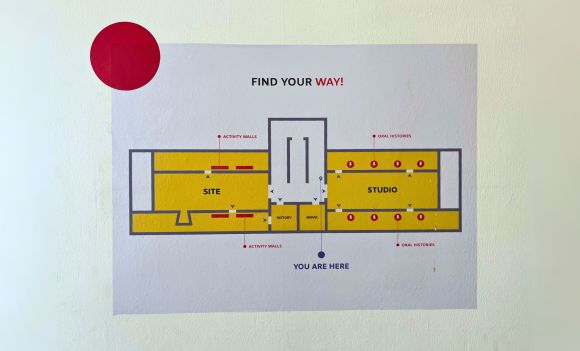

It’s funny how I was more aware of tattoo practices outside India than our own. Fortunately, that changed recently, during the India Art, Architecture and Design Biennale 2023.

Much like the Polynesian countries where tattooing different parts of the body holds meaning, tribes in central India too ink themselves with meaningful patterns and motifs.

Godna: Digging into Tradition

Godna is popular in tribal societies, particularly in the areas of Rajanandgaon and Surguja, Chattisgarh, Dindori, Madhya Pradesh and Madhubani in the Mithila region of Bihar.

My investigation into Godna led me to this short film by Shivam Vichare that shows the materials and motifs popularly used in the Baiga tribe in Dindori.

Using kajal (soot collected by burning herbal oil) and needles, ladies mark their bodies at various stages of life. Girls from the community must have their foreheads tattooed as preteens to be accepted into the tribe. Tattoos on the chest are made post marriage and childbirth.

Mangala Devi explains the meaning of some of the motifs—a form of prayer for the individual and family’s wellbeing. One pattern for the chest represents the beehive. Just as the beehive is dripping with honey, so may the home be full of nectar. Diyas on the knees signify light in their lives. And the bull’s eye is for the wellbeing of the cattle, so that they may plough the fields.

Like the Baiga Tribe, the Bharia, Bhil, Gond, Kol and Korku tribes hail from central India—home to some of the world’s oldest prehistoric cave paintings.

Many of the motifs used in Godna and other folk art are elements from nature. Expressed in simple line art, these symbols were created by the earliest graphic designers.

On display at the Biennale were some patterns from the collection of Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya (also referred to as the National Museum of Humankind, or Museum of Man and Culture) in Bhopal.

I don’t fancy myself ever having the courage to get permanently inked, but these patterns are beautiful and definitely worth ogling over. Enjoy!