Vinodeni had her task cut out. 30 minutes. Her newest clients didn’t have a moment more to spare. She shed her soft-spoken veneer and turned into the Willy Wonka of the Aquarium. “Okay! We have a short time, so I’ll prioritize and guide you through the most important exhibits.” She said, in an excited voice.

“Do you eat seafood?” Him, yes. Me, no. “Oh, no worries! I was asking because we’ll see some of the tastiest fish the Andamans have on offer. But hopefully, you’ll still enjoy it.”

The Aquarium next to the Aberdeen jetty is a small, likely under-funded museum dedicated to the marine life around the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. It wasn’t on our planned itinerary. But seeing that it was right next to our lunch place, and still had 30 minutes before closing time, we figured, why not? It was, after all, our last day at Port Blair.

We were welcomed into the otherwise dull-looking compound by a gigantic skeleton, displayed proudly to entice the casual onlooker. The entry to the main exhibits was through a small door. But first, we had to buy our tickets. And it was at the ticket counter, that my eyes lit up. Even if we didn’t go inside, my day was made. For by the ticket counter was the mythical creature my father told me about when I was a kid. But we had our tickets, and twenty five minutes to race through it all.

And that’s when we met Vinodeni, our museum guide.

Perhaps the word aquarium wasn’t an appropriate one. The inside of the museum looked more like a chemistry lab than a lively underwater showcase. Rows of shelves, stacked top to bottom with preserved specimens of marine life, each several years old. Vinodeni lamented the loss of some specimens during the tsunami, as she continued to show some not-so-appetising seafood in chemical filled jars.

Next up, the living exhibits. Vinodeni requested us to keep the flash of our cameras off, so as to not disturb the marine wildlife. The rooms were dimly lit, presumably to mimic the sea lighting, but the tanks themselves had artificial lights and bright colourful backgrounds.

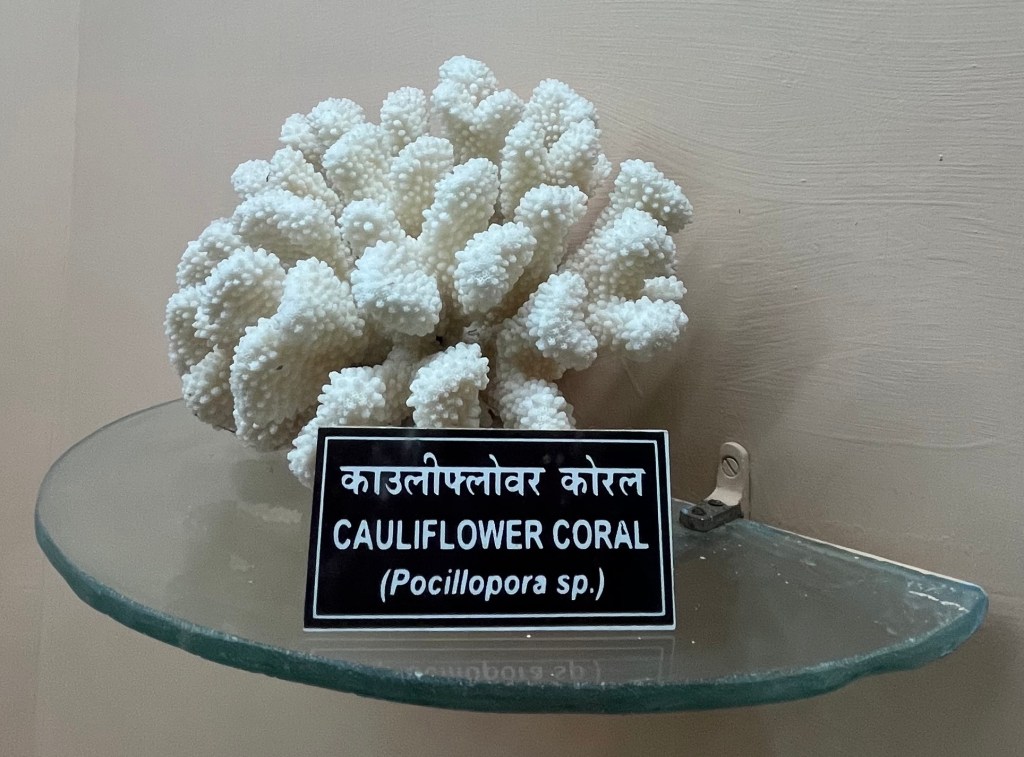

The fishes were beautiful, of course. But the exhibits I was most interested in were the seashells and corals.

I’ve been beach combing from the first time I visited the sandy beaches of Chennai. I’d admired my grandmother’s collection of small, pretty, colourful bones sorted neatly by type and displayed in fancy bowls. My mother’s collection had much larger ones, in various shades of brown. But it was my father’s collection that awed me the most. Almost entirely white and massive, these were deep sea creatures on our mantlepiece.

Several thousand kilometres away from home, in a dingy room, there they were, familiar faces. Now, thanks to the museum, I could give them names.

Vinodeni told us about how these exquisite creatures are now critically endangered. They’d been pulled out from their habitat and traded for their beauty. And now, there are too few of them in the wild. I flinched a little as she continued, “they don’t belong in our homes.” She then reaffirmed what we’d learned just a few days earlier—that even the abandoned seashells on the beach are reused by other creatures.

Vinodeni probably realised that I felt a little guilty, so she changed her tone a little and told us that those who acquired them in the past weren’t aware of what would happen. But now, the Government is trying to fix things.

It is now illegal to trade some varieties of shells. And the airport strictly screens baggage to catch anyone taking seashells and corals out of the archipelago.

Lunch time was creeping up, and mindful of the closing time, Vinodeni ushered us to the exit. “There is one more exhibit that you must see, but you’ll need to step outside in the sun for that.” We obliged. She took us towards the giant skeleton at the entrance of the museum. “This here, is a full skeleton of a Sperm Whale.” She then rattled off a quick set of facts about the creature, including why it was named thus. The way Vinodeni spoke made it abundantly clear that she was passionate about marine life.

With our tour over, we continued to chat for a while. I asked here where she was from, and she said she was from Port Blair. Her ancestors were from Tamil Nadu, but since she was born and brought up there, she considered the Andamans her home. “Wouldn’t you agree?” she asked me. After all, I too had grown up in Delhi, and though my roots lay in Madurai and Thanjavur, I was certainly more of a North Indian.

And perhaps that’s one reason why seashells excited me so much. It was that North Indian kid that was so enamoured by marine life so far away from where she grew up. Which is why I was excited by just standing next to the ticket counter. My seafaring father had told me about the fantastical creatures that lived deep in the ocean, especially the seashells the size of bathtubs. And seeing the Giant Clams in person was a dream come true.

Our trip to the Andaman Islands left a deep impact on me, particularly my relationship with seashells. I still adore them, and proudly display our collection at home. But ever since that trip, I’m mindful to not pick any more. They’re someone’s home, and they deserve to be used for that purpose for as long as possible.